Violence But Not Without Mercy

How Tolkien’s Legendarium differs from the Northern Sagas that inspired it

Mae govannen, friends! Josh here. This week we have a bonus post for everyone: a guest piece from , who has written here at the newsletter before. Amy has her own Substack at and is also a contributor to the Substack.

Today’s piece is a preview of a series she’s been working on over at Mythic Mind comparing the German saga Nibelungenlied to other mythic sagas, including Tolkien’s legendarium. Enjoy this preview of the series and be sure to check out the series if you want to read more!

Violence but Not Without Mercy

How Tolkien’s Legendarium differs from the Northern Sagas that inspired it

For the past few months, I [Amy] have been taking a deep dive into the old mythic sagas of northern Europe, beginning with the Nibelungenlied and comparing it to the earlier Volsunga Saga and Poetic Edda. These works had a major influence on J.R.R. Tolkien as he constructed his legendarium, but there were also ways in which Tolkien diverged from them. Those myths were full of bloodshed, but they were not sacrificial deaths meant to protect the innocent or lives taken in a battle over some point of moral principle. Treachery, bloodlust, revenge—these are the typical motivating factors in the slaughter of the northern European sagas.

The fictional world created by Tolkien is as full of evils as our own. People wrong each other and seek vengeance. Villains slay with wild abandon, and even the heroes ride into battle eager to shed the blood of their foes. But it is not simply the body count that sets the tone for a literary work: it is also the way violent deeds are interpreted. Here we will find the greatest difference between Tolkien and the pre-Christian authors who inspired him.

Tolkien’s saga begins with a perfect world in which slaughter is unknown. In a clear echo of the biblical tale of the Fall of Man, the lust for blood in Tolkien’s legendarium is introduced by spiritual beings who desire to usurp the powers of God and, after their fall from grace, seek to pervert the beings created in God’s image. Early on, we see a character of great brilliance, the Elf Fëanor, who though an enemy of Melkor (the Satan-like villain who tempts people to evil), is also quick to anger and hell bent upon revenge. When Melkor steals the Silmarils, a set of beautiful gems crafted by Fëanor, the Elf convinces his kin to swear an oath of blood that they will not rest until they have defeated Melkor and taken back the Silmarils. This sets in motion the main plot of The Silmarillion.

Whereas in the Nibelungenlied and the Nordic sagas, revenge is presented as morally ambiguous, Tolkien leaves the reader in no doubt that what Fëanor is doing is wrong. Almost as soon as they begin their pursuit of Melkor, Fëanor and his kin resort to stealing ships from the Teleri, another group of Elves. When the ship’s owners attempt to defend their property, it ends in bloodshed. “Then swords were drawn, and a bitter fight was fought upon the ships…Thus at last the Teleri were overcome, and a great part of their mariners that dwelt in Alqualondë were wickedly slain.”1 This first shedding of blood between Elves feels very much like the biblical story of Cain and Abel, and as Cain received a judgment from on high, so do Fëanor and his allies.

“Ye have spilled the blood of your kindred unrighteously and have stained the land of Aman. For blood ye shall render blood, and beyond Aman ye shall dwell in Death’s shadow. For though Eru [God] appointed to you to die not in Eä, and no sickness may assail you, yet slain ye may be, and slain ye shall be: by weapon and by torment and by grief…”2

We see this prophecy fulfilled through the rest of the book, and perhaps nowhere more so than in the Nirnaeth Arnodediad, a great battle of Elves, Men, and Dwarves against the hosts of Melkor (now renamed Morgoth). It begins with the brutal execution of a prisoner.

“And they hewed off Gelmir’s hands and feet, and his head last, within sight of the Elves, and left him. By ill chance, at that place in the outworks stood Gwindor of Nargothrond, the brother of Gelmir. Now his wrath was kindled to madness, and he leapt forth on horseback, and many riders with him; and they pursued the heralds and slew them, and drove on deep into the main host.”3

Here we see an extreme act of slaughter creating a desperate desire for revenge. Gwindor is driven mad with wrath and assaults the enemy lines, not truly to defend the cause of good, but to make his enemies feel the force of his anger and pay back evil for evil. Tolkien reveals the folly of Gwindor’s bloodlust in what happens next: though they meet with some initial success, the heroes are soon beaten back, and the battle turns into a mass slaughter, as seen in incidents like the death of the great Elven king Finrod. “Then Gothmog hewed him with his black axe, and a white flame sprang up from the helm of Fingon as it was cloven. Thus fell the High King of the Noldor; and they beat him into the dust with their maces, and his banner, blue and silver, they trod into the mire of his blood.”4

The Men are not immune from the slaughter. We read that, “Huor fell pierced with a venomed arrow in his eye, and all the valiant Men of Hador were slain about him in a heap; and the Orcs hewed their heads and piled them as a mound of gold in the sunset.” But here we see people motivated by something other than simple revenge. The story focuses on a man named Húrin, who as he sees the forces of darkness closing in around him, refuses to give in to despair. Even as his death seems certain, he kills the orcs who assault him, declaring with each stroke his hope for a better future.

“Then he cast aside his shield, and wielded an axe two-handed; and it is sung that the axe smoked in the black blood of the troll-guard of Gothmog until it withered, and each time that he slew Húrin cried: ‘Aurë entuluva! Day shall come again!’ Seventy times he uttered that cry; but they took him at last alive, by the command of Morgoth, for the Orcs grappled him with their hands, which clung to him still though he hewed off their arms; and ever their numbers were renewed, until at last he fell buried beneath them.”5

Here amid the tremendous bloodletting, we see something that never appears in the Nibelungenlied or the other northern European sagas: a belief in something stronger than ill fate. For though the evil will of Morgoth has dealt them a slaughter of epic proportions, characters like Húrin place their hope in a higher providence and the belief that God’s good intent for the world will ultimately prevail.

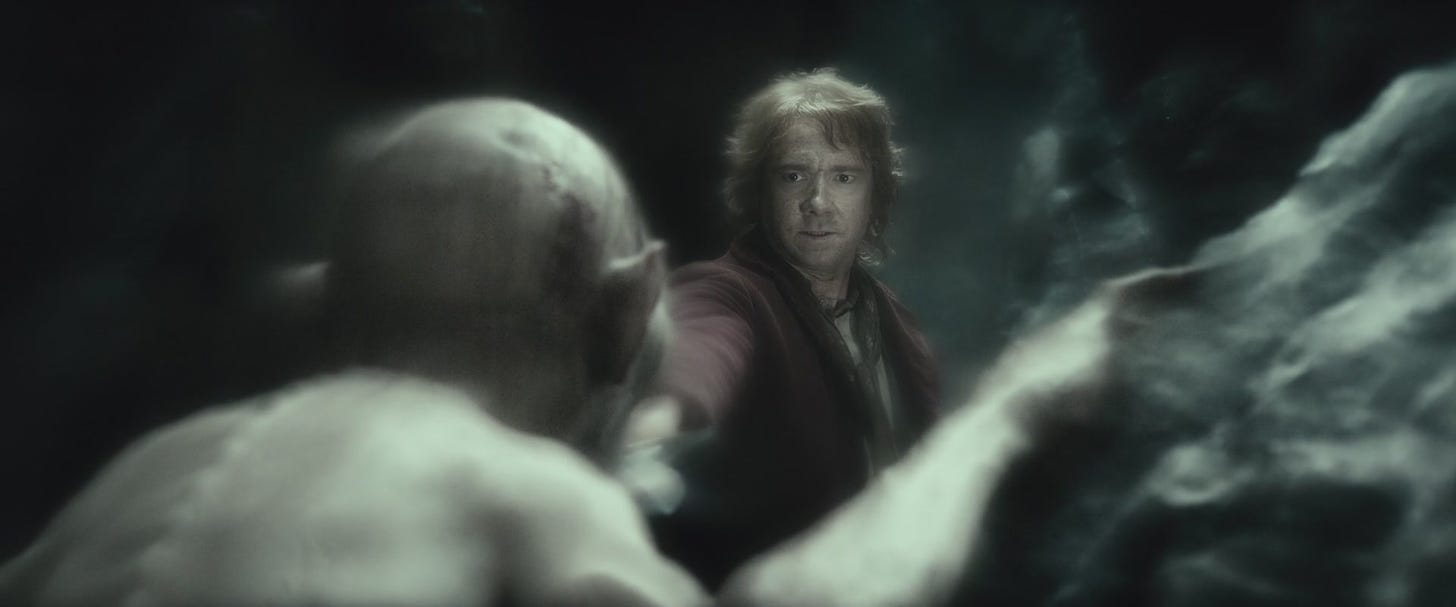

We see Tolkien’s emphasis on providence and mercy versus violence in one of the most critical plotlines of The Lord of the Rings: the finding of the One Ring and the quest to destroy it. Bilbo Baggins first recovers the Ring by accident in the dark tunnels beneath the Misty Mountains. It had previously belonged to a foul creature named Gollum, who when he realizes Bilbo has stolen his “Precious,” seeks to gain it back by violence. Bilbo discovers just in time that the Ring makes its wearer invisible and is therefore able to follow Gollum through the network of tunnels in the direction of the exit. Then comes a moment of decision as Gollum stands in the way of Bilbo’s escape.

Bilbo chooses to risk jumping over Gollum rather than killing him, a decision that proves fateful later in the story, for after Bilbo has grown old and passed on the Ring to his nephew, Frodo Baggins, Gollum is captured by Sauron and reveals the name Baggins to the enemy. When the wizard Gandalf informs Frodo of this fact, the poor hobbit is terrified.

FRODO: “O Gandalf, best of friends, what am I to do? For now I am really afraid. What am I to do? What a pity that Bilbo did not stab that vile creature, when he had a chance!”

GANDALF: “Pity? It was Pity that stayed his hand. Pity, and Mercy: not to strike without need. And he has been well rewarded, Frodo. Be sure that he took so little hurt from the evil, and escaped in the end, because he began his ownership of the Ring so. With Pity.”6

Pity. Mercy. These character traits are revered in Tolkien’s legendarium, but not in the northern European sagas that inspired it. In The Two Towers, Frodo and Sam are moving through a treacherous region near the land of Mordor, hoping to destroy the Ring in the fires of Mount Doom. There they capture Gollum, who has been trailing them for some time, ever lured by the power of the Ring. Part of Frodo still wants to kill Gollum, but he decides that the creature must not be harmed. “For now that I see him, I do pity him.”7

It is this act of pity that ultimately allows the Ring to be destroyed and Sauron to be defeated, for when he finally makes it to Mount Doom, Frodo is overcome by the temptation to claim the Ring for himself. It is only when Gollum tackles him, bites off his finger with the Ring still on it, and proceeds to fall accidentally into the abyss of lava below that the Ring is finally destroyed. Thus, we see the providential power of God working through pity and mercy to deliver an outcome that creaturely power could not have accomplished.

Therefore, the greatest difference between the Nibelungenlied, the Scandinavian sagas, and Tolkien’s legendarium is not how many people are slaughtered, but how that slaughter is presented.

Want to learn more about the connections between Tolkien’s work and the earlier mythic sagas? You can read the entire series, including a vastly expanded version of this article, on the Mythic Mind Substack page. You can also read Amy’s weekly reflections on her own Substack page, Sub-Creations.

To Discuss:

Are you familiar with any other mythic sagas from the past? How does Tolkien’s legendarium compare in your opinion?

Fëanor: love him or hate him? Or love to hate him??

Does Tolkien’s decision to have mercy and pity be the means that Good triumphs over Evil in The Lord of the Rings resonate with you? Why or why not?

Appendices

See you all on Thursday for the regularly scheduled newsletter! Farewell, friends. Go towards goodness!

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Silmarillion (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), 87.

The Silmarillion, 88.

The Silmarillion, 191.

The Silmarillion, 194.

The Silmarillion, 195.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lord of the Rings, Single volume movie tie-in edition (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1994), 58.

The Lord of the Rings, 601.

This was so fascinating! I think Eowyn is another interesting character to bring into this discussion because she really captures a lot of the Northern spirit in her desire to fight, so great deeds, and also in her despair. She struggles to see anything beyond the hope of dying gloriously in battle, and needs the hope Faramir offers her to remember that she should not love the sword for its sharpness, but should love that which the sword defends and protects. And I’m a big fan of loving to hate Feanor. He’s a fabulous character both because of his complexity and the way in which he feels like a figure in a Greek tragedy. And, of course, he’s very memeable

I really like this analysis. Tolkien's universe is ultimately not morally ambiguous, unlike that of his inspirations. I think it's interesting how much the Bilbo/Gollum stuff did not initially fit into the moral framework, given that the first edition of The Hobbit has Gollum wanting to gift Bilbo the ring as a present upon the losing the riddle game. We would not have the whole 'pity and mercy' discussion btw Frodo and Gandalf if the original version of the scene were still canon.